Karoonjhar as Kin

Areesha Khuwaja / Pakkhee

Community Collaborator: Dileep Permar

Some beings don’t speak in words.

The mountain is one of them.

Here, the land is not a backdrop.

It is memory, body, breath.

Karoonjhar doesn’t stand still for you to look at —

it reveals itself,

like a sentinel: alive, playful , and sometimes, wounded.

This page is not a record.

It’s a series of encounters —

where stone becomes kin,

water turns to story,

and wild herbs carry the scent of forgotten knowing.

What follows isn’t documentation.

It’s a kind of listening.

Maybe even a language —

to help us remember how to connect with the land again.

How do you meet a mountain on their own terms?

How do you listen until stone begins to speak?

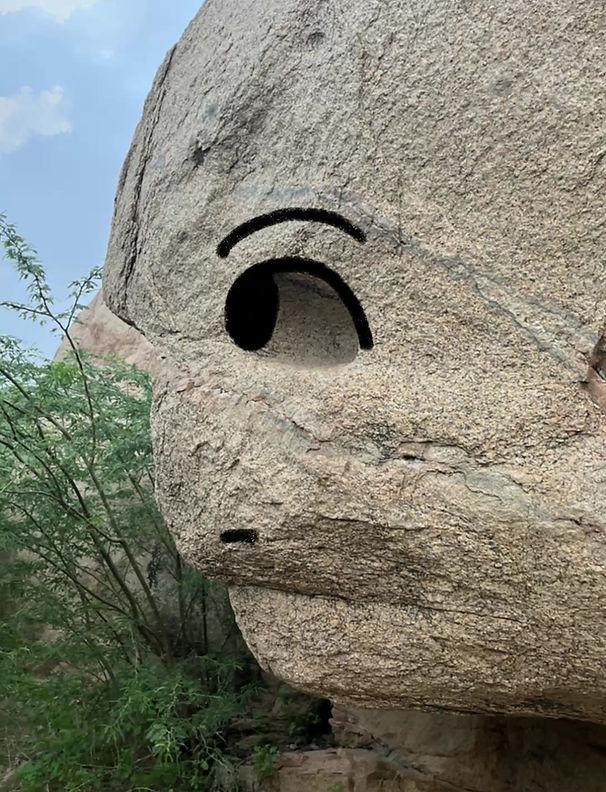

The mountain doesn’t show all at once.

Some forms stay hidden, waiting to be seen.

You are in nature’s museum.

These are not monuments —

they are shapeshifting installations,

carved slowly by time and wind and waiting.

The mountain rearranges itself

depending on the light, the season, the one who’s looking.

"There is a language beyond human language,

an elemental language,

one that arises from the land itself."

- Linda Hogan

What does it mean to receive the land in all its moods: playful, harsh, abundant, grieving?

Can tending to land as kin awaken rituals of care we have forgotten?

In allowing the land to transform us, do we begin to transform our future with it?

Like water, transformation is never still. It moves, carves, carries us forward.

Here, water turns to story.

In the time of the Jains, water was sacred. Never sold, never owned.

At Kajlasar, they say Jain women would bathe before dawn, their kohl lining the surface, staining the water with memory.

These are not ordinary rock formations.

The shapes of the granite matter hold rain, direct it, form waterfalls that still run clear and drinkable.

In a land where every drop counts, the hills remember how to gather and give.

These stones have also sheltered seekers.

For the Jains, the caves of Karoonjhar were places of meditation and enlightenment.

The mountain taught them how to sit with time, how to let stone, breath, and spirit flow together.

To frame land as scenery amputates its time signature.

The system severs bodies from soil, memories from place, voices from kinship.

Healing lives in remembering. In reconnecting. In soft slowness. In community.

Each year on Kanhooro (Krishna Janmashtami),

pilgrims from nearby villages carry the adorned murti of Krishna to a pond.

They sing as they lower him into the water.

And they walk back, singing Kanhooro Kodio, asking only this:

May your grace remain through all twelve months.

Around this same mountain, life continues in quiet devotion.

Cattle graze among the rocks.

Women farm nearby, their footsteps steady in the red soil.

The mountains give what they can:

water, inspiration, grass, shelter, medicine, rhythm.

Everything is received with trust.

Here, the mountain is not a metaphor.

It is a brother.

And so the people sing:

Doonger ne ni wado wecho, doongar maaro bha la

Don’t sell this mountain, the mountain is my brother.

A song passed from voice to voice,

from gatherings to quiet corners,

until it lives in every child’s mouth,

every woman’s call,

every man’s memory.

The mountains speak in the language of slowness. Presence is their grammar.

To listen is a practice.

May we begin.

Artist Statement

Areesha Khuwaja

Community Collaborator: Dileep Permar

My practice is guided by Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, who curated Sindh’s myths and folklore as portals of transformation. His verses speak of initiation and kinship; where help arrives from mountains for Sassui, from rivers and birds for Sohni. I inherit this worldview, and my language for expressing it is animism. With reverence, I create with the mountains, listening until their stories surface and their rituals breathe again.

In a world that severs bodies from soil and memory from place, my work becomes an act of remembering. Restitution is not only return but emotional: letting the mountain speak again, keeping the soil warm for seeds still waking.

In Echoes of Karoonjhar, our collaboration unites two lenses: Dileep Permar’s archival care and my ethnographic visual practice. Together we treat Karoonjhar as a living, shape-shifting archive of land-based cosmologies. Our work moves through time from the kohl-stained pond of Parinagar to the present grief of granite extraction, listening for what the land remembers when people are made to forget.

This collaboration is a refusal of erasure; a way of seeing, sensing, and re-membering for those who will come after us.

%20_edited.jpg)